Success in altering asteroid’s orbit after DART impact seeds hope in protecting home against such catastrophic intruders

Asteroids are big trouble for our planet’s safety. Remember the Chicxulub impactor catastrophe? That was caused by an asteroid impact with the force of 100 million megatons, which devastated the Gulf of Mexico region. Taking into account the massive loss experienced around 66 million years ago, NASA conducted a test called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) on September 26, 2022. The aim was to determine if we could redirect hazardous asteroids away from Earth. DART successfully impacted asteroid Dimorphos, demonstrating the possibility of altering an asteroid’s trajectory – and a new study has confirmed the mission’s success. This gives us hope that we are becoming capable of protecting Earth from big space rocks, like Apophis.

The DART mission’s success in changing the path of the asteroid Dimorphos is in fact a groundbreaking achievement in planetary defense. It’s the first time humans intentionally altered the movement of a space object.

“When DART made impact, things got very interesting,” said Shantanu Naidu, a navigation engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, who led the study.

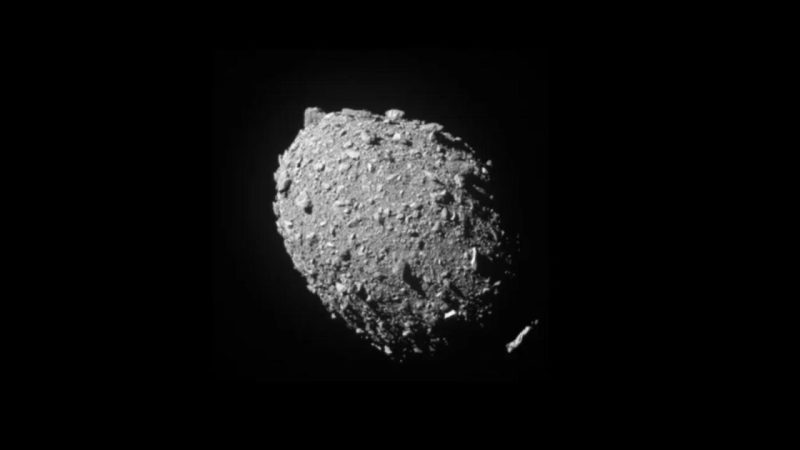

When NASA’s DART deliberately crashed into a 560-foot-wide (170-meter-wide) asteroid on September 26, 2022, it showed that a kinetic impactor could change the path of a hazardous asteroid, if needed to protect Earth. In this regard, a new study published in the Planetary Science Journal today reveals that the collision not only shifted the asteroid’s course but also altered its shape.

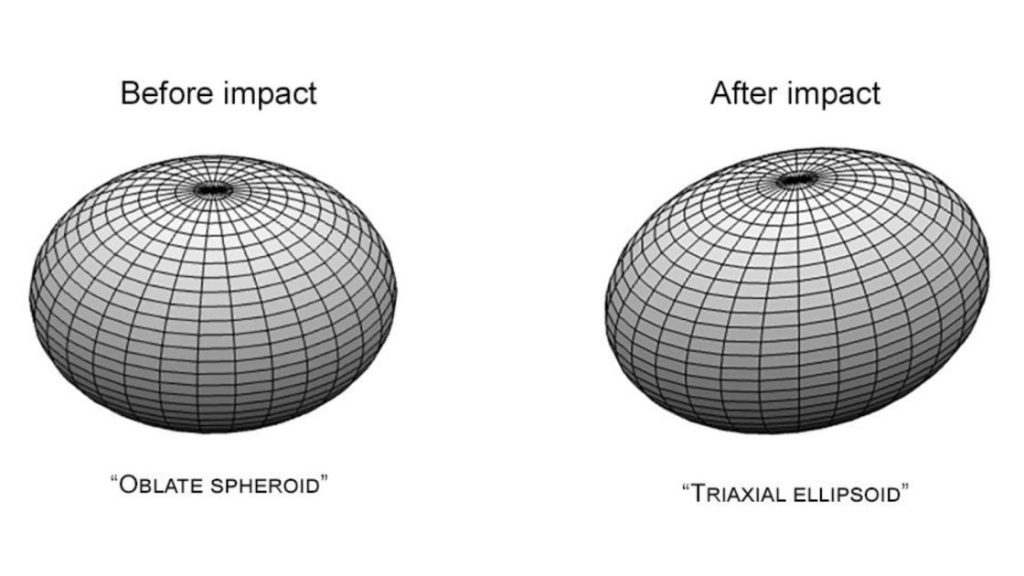

The impact of DART on Dimorphos, orbiting a larger near-Earth asteroid called Didymos, resulted in significant changes to both its orbit and shape. Prior to the impact, Dimorphos had a symmetrical oblate spheroid shape and a circular orbit. However, after the impact, its orbit became slightly elongated, and its shape transformed into a triaxial ellipsoid resembling an oblong watermelon. The team, led by Shantanu Naidu, a navigation engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), carefully observed and analyzed these changes.

The study used data from multiple sources, including images captured by DART as it approached Dimorphos, radar observations from the Goldstone Solar System Radar, and light curve measurements obtained from ground telescopes. The Goldstone Solar System Radar played a big role in tracking Dimorphos and its larger partner, Didymos, after the hit. The radar confirmed that DART successfully changed Dimorphos’ orbit around Didymos, shortening it by 32 minutes. Telescopes worldwide observed the brightness changes of Dimorphos and Didymos. The observations showed that Dimorphos got brighter by 2.29 ± 0.14 mag after the impact, indicating material release. Didymos returned to its original brightness in about 23.7 ± 0.7 days.

While the idea of an asteroid hitting Earth can be scary, the Torino Impact Hazard scale helps us understand the risk level. This scale, established by the International Astronomical Union in 1999, rates asteroids from 0 to 10 based on their likelihood of impact and the potential consequences. A rating of 0, labeled as “white,” means there’s either no chance of impact or an extremely low risk. It covers asteroids that will miss Earth and small objects that will burn up harmlessly in the atmosphere.

On the other hand, levels 8 to 10, in the “red” zone, indicate asteroids that are almost certain to hit Earth. Depending on the level, impacts could cause anything from localized damage to global catastrophe. Right now, there are no objects rated at level 0 on the Sentry Risk table. And some asteroids like Bennu and 1950 DA don’t have ratings because any potential impacts are more than 100 years away. NASA reassures us that there’s no significant threat of impact for at least the next century.

However, there could still be hazardous objects out there. That’s why organizations like CNEOS are always searching for near-Earth asteroids to keep us safe.

Ann the success of the DART mission in changing Dimorphos’ orbit by 32″ highlights our improving ability to shield Earth from space dangers. Using a kinetic impactor approach, the mission transferred momentum to Dimorphos upon collision, showing a practical way to deflect asteroids.

In addition to this, the data collected, such as the changes in trajectory and the release of over a million kilograms of rock, forming a tail tens of thousands of kilometers long, offer valuable insights into asteroid properties. This knowledge is essential for future missions, helping us refine models to predict potential impact outcomes.

Tom Statler, lead scientist for solar system small bodies at NASA Headquarters in Washington, stresses on the importance of confirming these findings independently strengthens the scientific community’s dedication to ensuring the accuracy of planetary defense strategies.

“Seeing separate groups analyze the data and independently come to the same conclusions is a hallmark of a solid scientific result. DART is not only showing us the pathway to an asteroid-deflection technology, it’s revealing new fundamental understanding of what asteroids are and how they behave,” Statler said.

The DART mission, led by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, has opened doors for humanity to protect itself from space hazards that have influenced our solar system’s history.

The mission was carried out under NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office. And the Deep Space Network (DSN), managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, handles communication and navigation for space missions. JPL operates under NASA’s Space Operations Mission Directorate at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C.