Chandra reveals Spider Pulsars’ terribly destructive act over nearby stars

Spider pulsars are the dead stars wreaking havoc on their neighbors. They strip companion stars through energetic particle winds, and Chandra’s recent findings, set to be published in the December issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, reveal their destructive nature on an extreme scale.

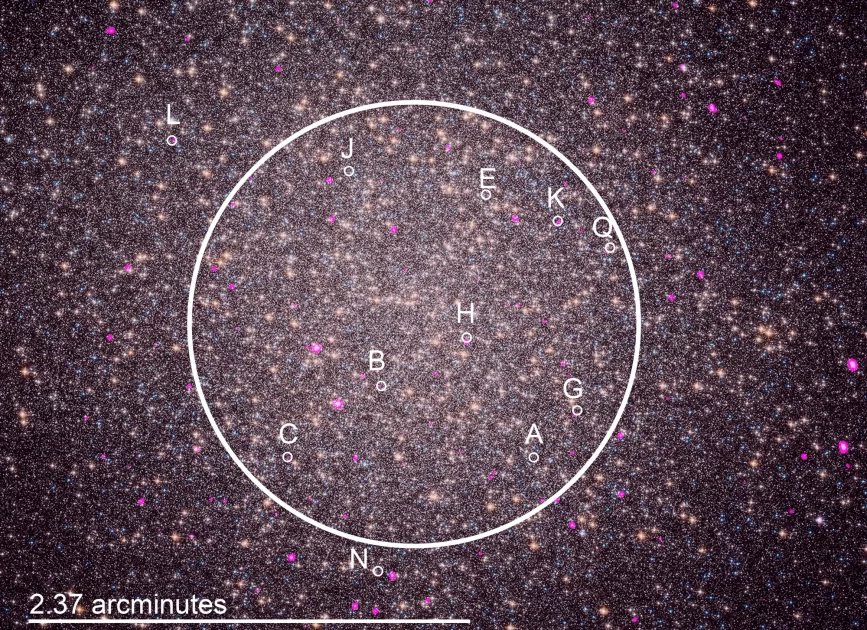

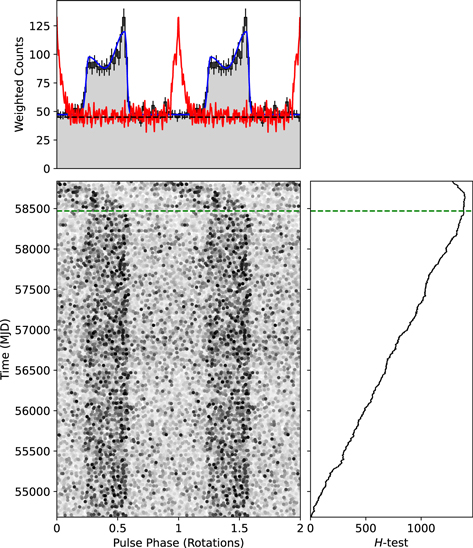

As described in the paper, astronomers discovered 18 millisecond pulsars within Omega Centauri using Parkes and MeerKAT radio telescopes. Chandra’s in-depth observation data highlighted 11 of these pulsars emitting X-rays, with five identified as spider pulsars near Omega Centauri’s core.

These spider pulsars come in two flavors: “redbacks,” targeting stars weighing 0.1 to 0.5 solar masses, and “black widows,” feasting on stars less than 5% of the Sun’s mass. Remarkably, the brightness of X-rays emitted correlates with the companion’s mass, revealing the impact of mass on the X-ray dosage these stars receive.

The X-rays generated in these scenarios occur when particle winds from the pulsar collide with matter from their companions. This collision produces shock waves akin to supersonic aircraft.

These neighboring stars endure a mere one to 14 times the distance between Earth and the Moon from the pulsars. This close proximity subjects them to substantial damage due to their closeness, according to NASA.

Chandra’s sharp vision is vital in understanding millisecond pulsar mysteries within globular clusters. Numerous X-ray sources clutter a small portion of the sky, challenging their differentiation.

In another study recently published in The Astrophysical Journal, astronomers have detailed 300 gamma-ray-emitting neutron stars. These include spider pulsars. As detected by the Fermi gamma-ray space telescope, these stars, rotating hundreds of times per second, act as precise cosmic clocks and potential tools for gravitational wave measurements and space navigation.

The discovery of PSR J1953+1844, or M71E, using the FAST telescope, provided essential insights into the evolutionary pathways between various pulsar types and their companions. Its tight orbit, mass, and location within the M71 globular cluster added layers to our understanding of binary pulsar systems.

Exploring multiband observations, including X-rays, and digging deep into evolutionary models, scientists aim to comprehend the nature and evolution of these cosmic duos further.

According to Thankful Cromartie, National Research Council Research Associate at the Naval Research Laboratory, these are such exciting results. “These low-frequency gravitational waves allow us to peer into the centers of massive galaxies and better understand how they were formed,” Cromartie said in a statement.